THE HISTORY OF TOMPKINS SQUARE PARKTHE HISTORY OF TOMPKINS SQUARE PARKTompkins Square Park has long served as a stage for the ongoing negotiation of public space in New York City. From its origins as Lenape land and colonial marsh, through 19th-century social reform experiments, to its pivotal role in the housing struggles, riots, and subcultural movements of the late 20th century, the park remains a site of tension between authority and autonomy, control and expression.

Tompkins Square Park has long served as a stage for the ongoing negotiation of public space in New York City. From its origins as Lenape land and colonial marsh, through 19th-century social reform experiments, to its pivotal role in the housing struggles, riots, and subcultural movements of the late 20th century, the park remains a site of tension between authority and autonomy, control and expression.

EARLY HISTORY: LENAPE LAND AND A SWAMPY BEGINNING (PRE-1830S)

This land was once part of Manhattan’s largest salt marsh, a tidal wetland teeming with life . The Lenape people fished and hunted in these coastal marshes for generations, capitalizing on the “high productivity” of the brackish ecosystem, a habitat where freshwater and saltwater converge. In 1834, New York City stepped in to create a public square here. The land – still a “swampy” parcel from the estate of colonial governor Peter Stuyvesant, was purchased for $93,000 and then drained, filled, graded, and planted with trees.

This project, part of the 1811 Commissioners’ Plan, was intended to uplift an “unfortunate” part of the city and spur development in the surrounding area . By about 1850 the transformation was largely complete: Tompkins Square (named for Daniel D. Tompkins, a former NY Governor and U.S. Vice President) was officially a park, albeit one born from muddy origins.

Ratzer Map (1776) A Plan of the City of New York in North America

The park officially opens in 1834. Rather than the elegant neighborhood envisioned by planners, Tompkins Square became the heart of a working-class immigrant district. The local “Dry Dock” area bustled with shipbuilding and industry, attracting waves of Irish laborers and later German immigrants (in what became known as “Kleindeutschland” or Little Germany). The park, one of few green spaces on the Lower East Side, quickly filled with children and families seeking fresh air. By the 1850s Tompkins was used as a militia drill ground and gathering site for mass meetings, with public speakers and protesters exercising free assembly.

19TH CENTURY: IMMIGRANTS, UNREST, AND REFORM

People enjoying (most likely) German music and entertainment in Tompkins Square Park, 1891. An image from Harper’s Weekly by Thure de Thulstrup.

MILITARY PARADE GROUND

The military’s needs for the park often conflicted with those of local residents. Although Tompkins Square had been nicely renovated in the late 1850s, much of the park’s landscaping had inevitably been destroyed by Civil War troops briefly encamped on the site in 1863. Soon after the war, unhappily just after renovations had been completed in 1866, the state legislature ordered the city of New York to ‘remove all trees and other obstructions’ so that a military parade ground could be built for the Seventh Regiment of the New York National Guard!’

That summer the trees were removed and the ground regraded, and by fall the square was put to military use As the city’s largest public square, the 10-acre site seemed an ideal spot for regimental and drill parades. And even if the neighbors objected, they wielded too little power to defend their park.

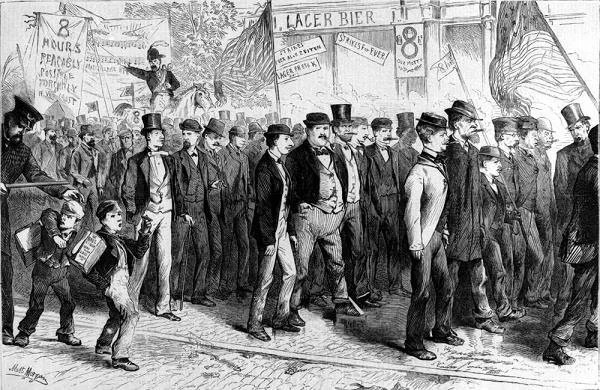

Illustration of the 1874 protests, notably featuring a German establishment in the background.

A condescending illustration of Tompkins Square Park from the New York Journal Hearth and Home, 1873. (NYPL)

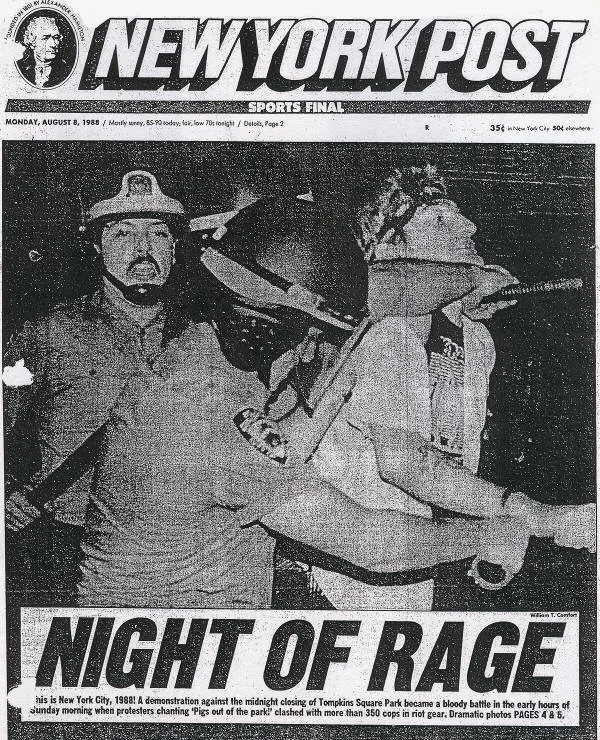

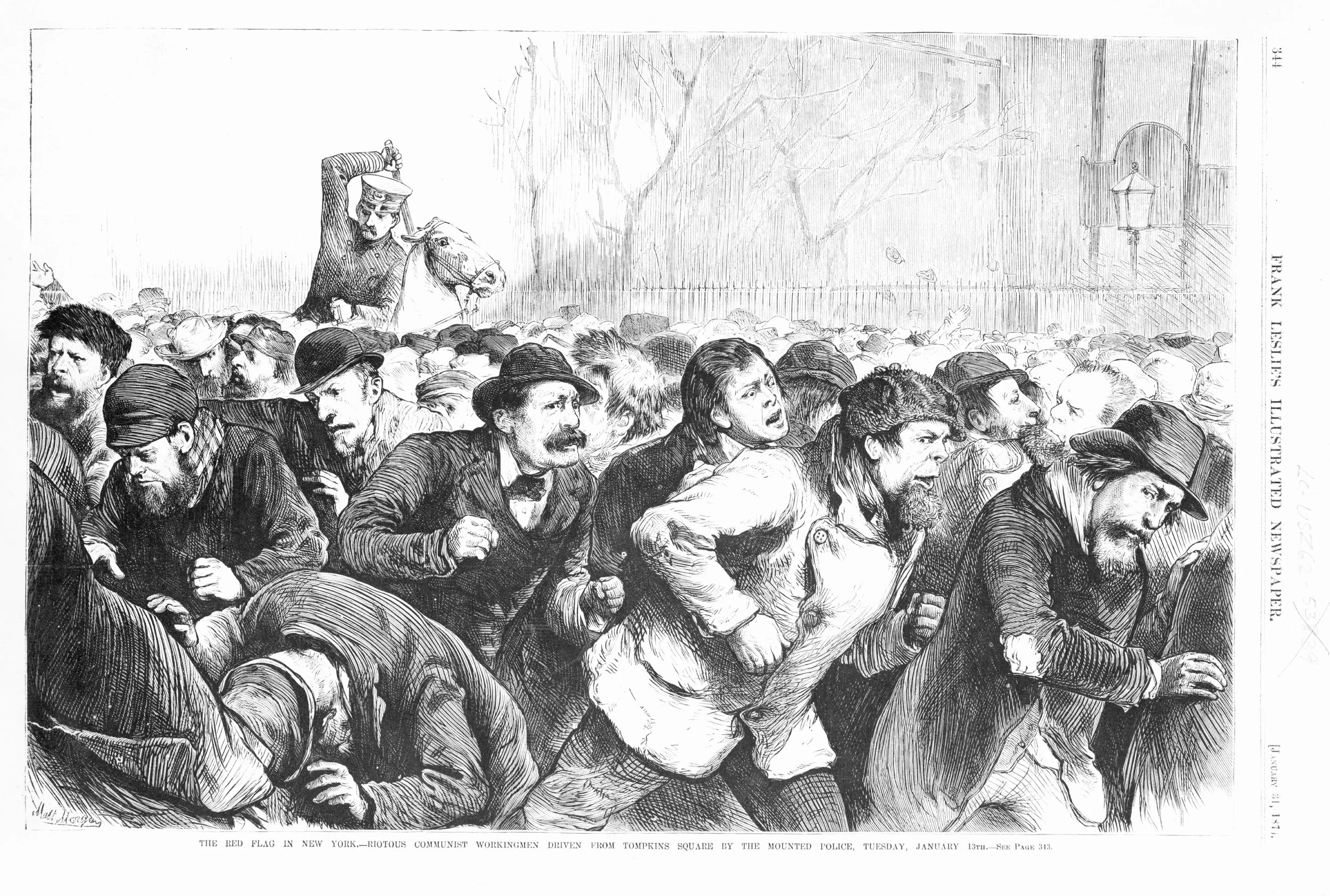

Economic depression hit in the 1870s, and with it came unrest. On January 13, 1874, some 10,000 unemployed workers assembled in Tompkins Square seeking relief. Overnight, authorities had pulled their permit. That morning, as confusion spread, legions of police on horseback plowed into the crowd swinging nightsticks, dispersing thousands of demonstrators into the surrounding streets. This sudden violent crackdown – the first Tompkins Square Riot – shocked the city. It was seen as an attack on the working poor and on the emerging labor movement. In response, locals defiantly affirmed the right to free assembly, passing resolutions that the park must remain open to “the people”.

TOMPKINS SQUARE RIOT 1874

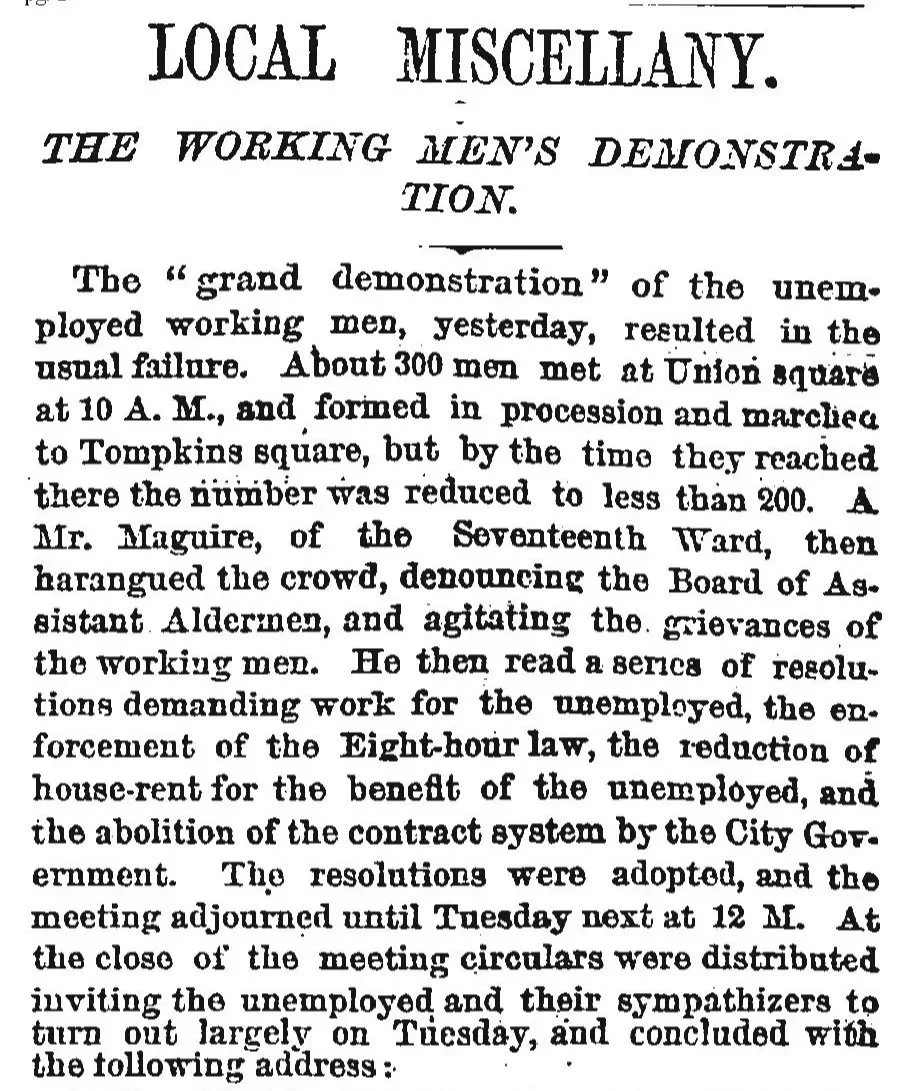

The New York Times, January 9, 1874

The Red Flag in New York - Riotous Communist Workingmen driven from Tompkins Square Park by the Mounted Police

RECLAIMING AND BEAUTIFYING THE PARK

By the 1870s the park was a dusty mess. Famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted of Central Park and Prospect Heights was consulted on adding paths, benches, flowerbeds, and a fountain. By 1878, the entire 10-acre square was restored to park use. 450 new trees were planted, lawns seeded, and 160 gas lamps installed, transforming Tompkins Square from a “forsaken waste” into a green oasis with a music pavilion at center.

Celebrations that year drew 10,000 people, with singing societies and brass bands heralding the park’s rebirth. The German-American community’s influence was strong – the park was nicknamed “Weisse Garten” (“White Garden”). This era also saw the installation of monuments that still stand today, like the Temperance Fountain (a classical drinking fountain donated in 1891 to promote water over alcohol) and the planting of stately American elms along the paths.

The Temperance Fountain is made of cast iron and was once topped with a statue of Hebe, the Greek goddess of youth and cup bearer to the gods. The fountain once had red, white, and blue stained-glass lamps. It’s one of the oldest surviving features in Tompkins Square.

Installed in 1888 by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, a group that wanted people to drink water instead of alcohol. At the time, the East Village was full of bars and beer halls, and the fountain was meant to offer a clean, free alternative, especially for working class men.

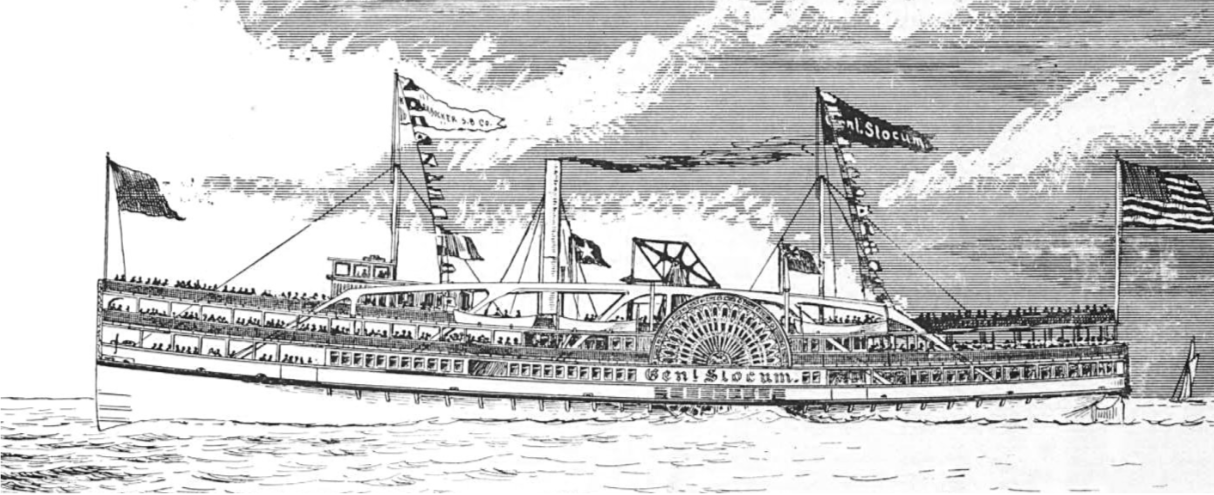

SLOCUM DISASTER (1904)

The St. Marks Lutheran Church charters The General Slocum, a steamboat, for the annual church picnic at Locust Point, Long Island. 1,358 church members, mostly women and children board the ferry at the East Third St. docks. Fire breaks out on board by Hells Gate on The East River and the ferry cannot dock on the NYC side of the river without the fires spreading through the lumber yards and oil tanks. The ferry is beached on North Brother Island and 1,021 people are dead. Many of the fathers, husbands, and brothers were lining the shore as the disaster unfolded. Most of the Germans moved uptown after the disaster to Yorkville.

An illustration of The General Slocum docked in the Rockaways late 1800s

Diagram of the course taken by Captain Van Schaick from the moment he discovered the fire until he beached his boat south of Rikers Island. The solid line shows the course sailed. The dotted lines and stars show the spots where, according to river men, the captain could have beached his boat and saved much time.

PROGRESSIVE ERA REFORMS

Tompkins Square Park evolved into a hub for social reform. With the arrival of middle and upper class reformers in the East Village, the park’s purpose expanded beyond recreation and became a tool for shaping civic values and public health, especially among immigrant children.

In 1894, it became one of New York City’s first public playgrounds. Reformers Lillian Wald and Charles Stover, founders of the Outdoor Recreation League, staffed the park with trained leaders who organized structured play to keep children out of the streets and instill discipline, character, and hygiene.

The opening of the Tompkins Square Park children’s garden in 1934. (NYC Parks Archive)

Boys Playing Basketball on a Court at Tompkins Square Park on Arbor Day, New York, 1904

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, Tompkins Square remained essential to the neighborhood—a refuge for children and a platform for labor organizing and political speech. On peak summer days, more than 1,200 children passed through. During the Depression, its significance led to major renovation efforts, further cementing its place in the life of the working class.

Surrounding the park

a network of social institutions emerged

The Boys’ Club of New York (1876)

The Children’s Aid Society Christodora House (1897)

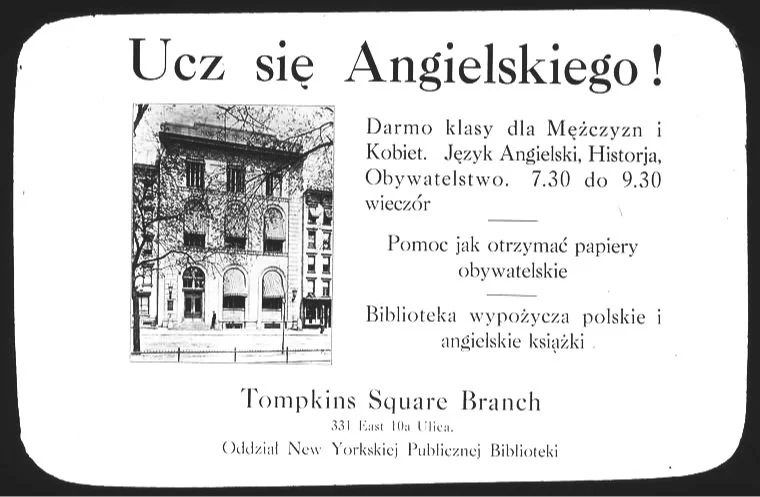

Tompkins Square Public Library (1906)

Polish flyer for English classes at the Tompkins Square Branch library.